In 1960, a prescription drug designed to suppress ovulation and inhibit conception — widely known and universally referred to as The Pill — liberated a generation of women, allowing them to take control of their sexual health for the very first time in history.

If you came of age in the ’80s or ’90s, your provider likely floated The Pill as your best bet for birth control — and there were many formulations to choose from, making it a flexible, easy choice for many.

In 1970, an American-made intrauterine device, or IUD, debuted with the sci-fi-esque name Dalkon Shield, and with it came a series of fatal flaws (sometimes literally), including a braided cord that invited infection, which potentially caused the onset of infertility. There was also disagreement among professionals about what to do in case of unintended pregnancy.

As a result, there were reports of maternal death after miscarrying, and consequently numerous lawsuits, in which juries awarded millions in damages.

Not long after, there was what amounted to an unofficial nationwide recall of the IUD, and just about a decade after its American debut, the IUD was virtually impossible to find in the U.S.

So, if you came of age in the ’80s or ’90s and your sex ed class treated the IUD as a weird, fringy choice — the copper IUD debuted in 1984, but it took four years before it was offered in the U.S. — that’s because, well, it kind of was.

Automatic and effective

But now that has all changed. And there’s a lot to catch up on.

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, the professional membership program for obstetricians and gynecologists, began recommending IUDs in 2009 as its first-line recommendation for patients — ranging in age from adolescent to perimenopausal — who were seeking long-acting reversible birth control methods.

The organization reiterated its unstinting support for IUDs in 2015 and again in 2017 because, it said, long-acting reversible birth control methods (such as IUDs and upper-arm implants such as Nexplanon) are up to 20 times more effective than pills, patches or rings in the long term.

Now Minnesota physicians are echoing that sentiment.

“IUDs are where it’s at,” said Dr. Kristin Lyerly, an OB/GYN at Maple Grove Hospital. “It’s the best method out there, hands down, because it works for so many women,” Lyerly said. “And the beauty is that it’s better than 99 percent effective, but also totally reversible.”

More than 99 percent effective puts it on par with female sterilization (tubal ligation), which is permanent.

The IUD is ideal for postpartum moms, even if they’re breastfeeding or considering another child, Lyerly said.

“I love doing IUDs for postpartum moms, right at the [standard, six-week] postpartum visit,” Lyerly said. “Postpartum moms don’t need another thing to think about.”

Dr. Maureen Ayers Looby, an OB/GYN who practices at Fairview Lakes in Wyoming, Minnesota, concurs.

“The IUD completely takes out human error, constantly working for you every day,” she said.

And that’s important for women juggling life with a newborn.

“You’re not even sure what time it is — or you’ve been awake two days in a row — why add another task to remember?” Ayers Looby said, adding that many popular birth control methods fall far below the 99 percent effective threshold.

For example, the average couple who uses birth control pills correctly over a year still has a 9 percent risk of getting pregnant. Correct use of condoms has an 18 percent failure rate. And natural family planning, also known as the rhythm method, carries a pregnancy risk of up to 24 percent.

Despite the IUD’s effectiveness, only 7.7 percent of women in the U.S. using contraception in 2015 reported having an IUD, according to data from the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

A little plastic T

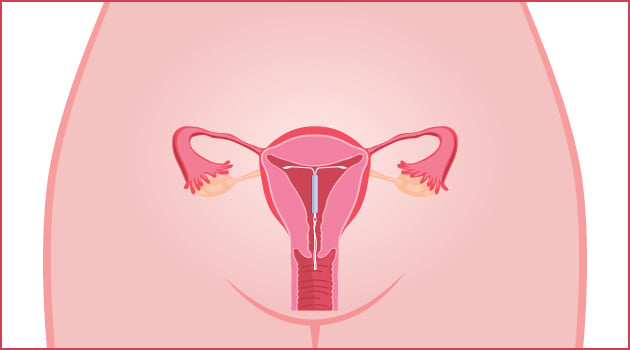

The IUD works, in part, by creating an “inhospitable” environment for a sperm and egg to meet and implant in the uterus.

About 1 inch tall and wide, IUDs are flexible T-shaped devices. When compared to the jellyfish-like Dalkon Shield — with its plastic ring, central membrane and lateral spikes — modern IUDs are triumphs of simplicity.

There are two main types approved for contraceptive use in the U.S.

First, there’s the ParaGard, a non-hormonal copper IUD that relies on the spermicidal nature of copper (pictured above).

Though the method offers completely hormone-free birth control, some women experience heavier bleeding and cramping than their regular periods.

Of note: If the copper IUD is inserted up to five days after unprotected sex, it’s 99.9 percent effective at preventing pregnancy, making it an emergency contraceptive option with lasting protection.

Another feature: ParaGard lasts at least 10 years, if not 12.

The second option is the hormonal IUD, of which there are now four models — the very popular and well-known Mirena, and the newer Kyleena, Skyla and Liletta. This type of IUD uses a small amount of the hormone progestin, which thickens cervical mucus, discouraging sperm from entering the uterus. It sometimes prevents ovulation as well. Finally, the lining of the uterus doesn’t build up much blood, so many women report that, after initial spotting, they have much lighter periods or — and this is a big one for many women (for better or worse) — no periods at all.

What’s the difference?

Hormonal types vary by dosage, size and duration of use.

Mirena (52 mg of hormone, pictured above) and Kyleena (19.5 mg) both last for a minimum of five years. Skyla (13.5 mg) lasts for three years.

Kyleena and Skyla are slightly smaller than Mirena (1.18 inches versus 1.26) and are geared toward women who haven’t had children.

All three are made by the Bayer pharmaceutical company. Generally speaking, the higher the level of hormone, the higher the likelihood is that the user will get lighter periods or stop getting periods altogether.

Liletta (52 mg) is similar to Mirena, but is currently approved for only four years of use before replacement and is a made by Allergan pharmaceutical company in partnership with the San Francisco-based nonprofit female-led pharmaceutical company known as Medicines360.

Medicines360 — which is focused on women’s health worldwide — recently introduced a hormonal IUD known as Avibela in Madagascar. Sales of Liletta in the U.S. help fund research and development to bring family-planning solutions to countries around the world.

Mirena’s magic

The most popular hormonal IUD choice remains Mirena, despite the influx of new options on the market. It was approved for use in the U.S. in 2001, more than a decade after it was introduced in Europe.

“It’s my favorite for my patients,” Ayers Looby said. “It’s been around the longest, so there’s really good safety data about it.”

Mirena also boasts the longest continuation rates, meaning most women take it out only to replace it or get pregnant.

Women have flocked to the IUD for another major benefit: The amount of hormone exposure from an IUD is far less than that of birth control pills.

“Picture taking The Pill,” Ayers Looby said. “You have to swallow it and digest it. It then goes into your bloodstream and then acts on your uterus and ovaries to prevent ovulation. Once it’s in your bloodstream, it can cause systemic side effects.”

Sometimes those effects are highly desirable, as is the case for acne control.

But birth control pills, Ayers Looby said, can also cause all sorts of unintended systemic side effects, such as decreased milk supply for breastfeeding mothers and an increased risk of blood clots with some formulations.

Because IUDs release hormones directly into the uterus, only small amounts enter the bloodstream.

Additionally, there are generally two types of female hormones in birth control pills (estrogen and progestin), but hormonal IUDs rely on only one (progestin).

Broader implications

Jennifer Schrader, a 36-year-old mother of two from Minneapolis, is a Mirena evangelist.

“The thing that I like most about Mirena is that I don’t have to remember to take anything, and the lack of periods or lighter periods are definitely helpful,” she said, adding that Mirena is far and away her choice until her doc says it’s time to be done. “I’ve been on pretty much every form of birth control other than the Depo shot. Pills, patches, rings — done, done and done.”

Not having periods makes for more flexibility with her wardrobe — and her sex life.

“There are so few things in our postpartum lives that can make us still feel feminine and desirable,” she said. “I’m not giving up my thongs.”

Even mothers consulted for this story who suffered the rare instances of IUD complications — such as uterus perforations, expulsions and/or migrations — said their experiences wouldn’t stop them from recommending IUDs to others, or trying them again.

Additionally, the hormonal IUD is being used for perimenopausal women and women with endometriosis (and other conditions) to control their symptoms. They’re also a choice among women with cognitive or physical disabilities and among homeless women, too, owing to their long life, the need for fewer doctor visits and feminine hygiene products and ease of use.

Women who are facing cultural or religious issues or domestic violence — who need birth control without their partner knowing — can safely choose IUDs as a discreet birth-control option.

Online mythology

If you use Google to do your IUD research, beware: The Internet is rife with horror stories about all types of birth control (so are Internet-based moms’ groups).

Relax, say medical professionals. The data simply doesn’t support the proliferation of this online mythology.

“There is a whole group of people who love, love, love it — and a handful of people who have had a sister’s boyfriend’s mom have a problem,” Ayers Looby said.

Karen Zimmerman, a certified nurse midwife with HealthEast in the Twin Cities, said the social media storyline and the reality in her practice just don’t match up. Nearly all the patients she sees are satisfied with their choice, and she’s seen very little dissatisfaction with the method.

In fact, IUDs are now the most common contraception she prescribes.

Looby agreed: “The vast majority of those who are confident with the data and trying the method are happy with the choice.”

A sociopolitical response

In addition to the medical community paving the way for broader IUD acceptance, there’s another factor afoot: Fears about a loss of reproductive rights have risen since the 2016 presidential election.

There are multiple facets to these concerns: The possible repeal of the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare), threats to Planned Parenthood’s Title X funding and the potential for anti-choice Supreme Court nominations, which some believe could open the door to a rehash of

Roe v. Wade and abortion rights.

In January 2017, Slate reported that Planned Parenthood saw a 900 percent increase in patients seeking IUDs in the week after the election. Women urged their friends on social media channels to book appointments for IUDs to capitalize on what remaining covered reproductive health care they may have left. Others talked of stocking up on Plan B pills and pushed for immediate monetary support of Planned Parenthood.

After the election, Zimmerman saw an influx of women saying they were worried about their contraceptive choices and the future of their medical insurance.

Lyerly said the cost of IUDs — which Planned Parenthood puts at $0 to $1,300 — is a factor, too: “Women are very concerned they will not get their birth control, and IUDs are not un-expensive.”

More than a few Twin Cities women have seen the election as a call to action to choose IUDs.

“I got mine put in right after Donald Trump was elected president,” said Heather Friedli, a 35-year-old mother of two from St. Paul who hopes her five-year IUD will outlast the current president. “I felt it was important to have a semi-permanent method this administration could not take away from me.”

A couple caveats

As always, it’s a good idea to consult your doctor or health-care pro about what contraception method is right for your body and life situation.

It’s important to note that IUDs do nothing to prevent the spread of sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Side effects of IUDs include pain during insertion (which some women describe as excruciating while others say it’s next to nothing), plus cramping or backaches for a few days after insertion; irregular periods; spotting between periods; ovarian cysts; and — with ParaGard — heavier periods and worse menstrual cramps.

In rare cases, an IUD can attach to or go through the wall of the uterus and cause other problems. There is also a low risk of a serious infection called pelvic inflammatory disease (1 percent) and a risk of accidental expulsion (4 percent).

Also, IUDs aren’t entirely maintenance free. It’s recommended that users do monthly string checks to make sure the device is in place. Women often report that the strings aren’t always easy to feel, even when present. If you’re concerned, your OB/GYN can do a check for you.

If you’re interested in getting pregnant, you can start trying as soon as you see your doctor to have your IUD removed. According to Mirena and independent research, 8 out of 10 women who want to become pregnant succeed in becoming pregnant within a year of having an IUD removed.

Just remember, the IUD can’t stop time, so while it doesn’t affect your fertility per se, your eggs will still continue to age — and decline in number — while the IUD is in place.

Katie Dohman is a freelance writer and mother of three who lives in West St. Paul. She’s always been scared of the IUD, but now she’s been convinced it’s a safe option.