A couple years ago, a conversation sparked a change in the way I teach. As the last fourth grader trailed out of my classroom for the day, some fellow teachers and I gathered in the hallway to hash out the day’s events. One coworker talked about an activity he tried that day that his class couldn’t handle — the students were just too talkative and unfocused. “Maybe next year you’ll have a class that can do it,” I commented, our standard response when we had those days where we couldn’t get students to hook into a lesson. And I’ll never forget what another coworker said next: “I don’t know,” she began, “I think this is the new norm.”

That moment has frozen in time as a touchstone for me. It was the moment that opened my eyes to the fact that our community of kids in general has changed. There are many reasons why the culture of behavior and learning is different now than it was even 10 years ago, but it wasn’t until I discovered the presence of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) that I began to seriously rethink how I taught.

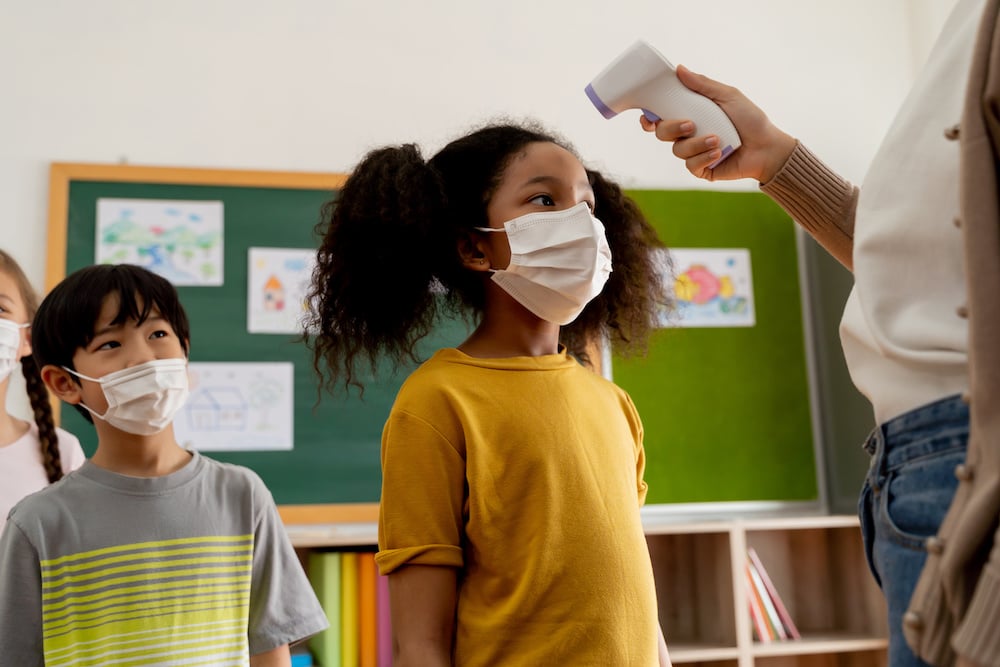

When I zoom forward to our current education situation, the consideration of ACEs is even more important for anyone teaching kids. Everything in our students’ worlds has changed drastically this year (e.g., distance learning, hybrid learning, masks, group separation and isolation) and will continue to change throughout the foreseeable future.

Prior to the pandemic, one theory contributing to the ever-so-noticeable changes in students in the past decade includes the residuals of the No Child Left Behind Act as well as a statewide shift to all-day kindergarten. The education world has put a heavy emphasis on academic rigor to prepare for state tests, which has resulted in a lack of play.

In Pasi Sahlberg’s book, Let the Children Play, he discusses the fundamental need for free play and fresh-air recess. The lack of unstructured play at school is resulting in a community of kids who are unable to sit still, solve problems socially and display the same sit-in-a-desk-listening-to-a- lesson stamina that kids did so obediently “back in the day.”

Another contributing factor stems from the fact that the number of children dealing with trauma is on the rise. I had noticed in the last few years that even my tried-and-true behavior consequences were not having any effect on certain kids. And what us teachers once chalked up to be a general lack of respect for authority and enabling and/or lack of parenting at home needed to be reexamined.

I’m embarrassed to admit it wasn’t until last year that I learned the term ACEs. According to the ACE study done in 1995, and again in 2019, there are basically 10 categories of personal or household abuse, neglect and other traumas that deeply impact children’s ability to regulate emotions and learn in school. According to the ACE Interface Presentation, brains develop and adapt differently as a result of such traumas.

After learning the basics of ACEs, I began to consume everything trauma-related that I could get my hands on: reading Notching Up: The Nurtured Heart Approach by Howard Glasser and The Connected Child by Karyn Purvis, taking a class in Trust-Based Relational Intervention (TBRI) and becoming an ACE Interface Trainer. Applying what I had learned, I started to see little glimmers of hope with some tough kids in my classroom.

These sparks of success led me to believe there is hope for kids dealing with ACEs. According to trauma-informed practices, kids need several trusted adults building relationships with them to gain the resilience they need to overcome certain traumas. Depending on the parent situation at home, this may mean that the role of other family members, teachers, coaches, neighbors and community members becomes crucial to help kids succeed.

Being mindful of ACEs, here are some of the biggest successes I’ve seen in the classroom and as a parent:

TEACHING SELF-AWARENESS AND SELF-REGULATION

Karyn Purvis and the TBRI model talk about checking your “internal engine.” We need to teach kids how to be aware of how they are feeling. Many children who have experienced adverse situations are in constant survival mode. They are often unaware of their emotions and even basic needs such as hunger and thirst. I’ve been guilty of being the tough disciplinarian when a child is acting out, but when I heard that dehydration can often cause aggression, I felt shocked. Maybe I didn’t need to get tougher … but rather hand them a water bottle.

EYE CONTACT/TALKING TO THEM ON THEIR LEVEL

Over the years, movies and TV have portrayed teachers and parents maintaining their authority by standing over a child. It’s easy as a teacher of a large classroom to fall into the habit of shouting commands across the room, or to stand over a student when questioning their disruptive behavior. Trauma-informed models have shown that part of strengthening a caregiver relationship is connecting through eye contact at the child’s level.

THE REDO/RESET

I frequently forget that children are not preprogrammed to know what we as adults have already learned the hard way — for example, how to speak respectfully. On the way out of Target last year, a kind employee waved goodbye to my then 4-year-old son. He was in a silly mood, so he called over his shoulder, “Bye, tootie-butt.” (Yep, we were in that phase.) My gut reaction was to snap at him, take something away or otherwise punish him, when I realized he doesn’t know that kind strangers working at Target might not prefer being addressed as a tootie-butt. Instead I said, “Whoops, we don’t call people that. Let’s try it again. How about just: Bye!” I read about the reset in The Nurtured Heart Approach. And kids with ACEs have a low threshold for frustration already! When they don’t understand how to act and get punished, it furthers that frustration and often results in an anger explosion.

MORE PLAY!

As I mentioned earlier, increased demands from standardized testing and common core pressure has caused free play and recess to be on the chopping block in the traditional school day. Educational researchers are finding that lack of play is directly contributing to increased challenging behaviors in the classroom. They discovered that when kids do not have the social and physical benefits of enough play, they have fewer coping and resilience strategies for the trauma they have experienced. Especially now, as most children have experienced some level of social isolation due to the pandemic, fresh air and free play are important for healing!

What I love about these strategies is that they are good for all kids, heavy trauma or no. Things like building relationships, providing more strategies for problem-solving and allowing kids to learn from mistakes are all things that we should be teaching our children.

I know some people in the education world think schools have gone “too soft.” They believe we are constantly bending over backwards for kids with any sort of challenge, unique belief or emotional hardship. Yet the truth is — there is such power in perspective. For example, rather than making assumptions about the behavior of tough kids, we can shift our thinking to wonder the cause of that behavior. It’s changing from “what’s wrong with that kid?” to “what happened to that kid, and how can I help?” Anyone who has worked with children knows that kids today are dealing with far more than most of us did at their age.

Whether a child has thrived or struggled throughout the last year, dealing with issues of quarantine, isolation, hybrid or distance learning, etc., is a level of trauma. At the moment of writing these words,

I am a bit over a month into our latest school year. It’s different than any year I’ve ever taught, but one thing is clear — we are in the midst of raising some of the most resilient and persevering humans our culture has ever seen. And I can’t wait to see how they change the world.

Susan Wangen is a Minnesota native and a fourth grade teacher in the southwest suburbs. She lives with her husband and two kids, Charly and Auggie.